Occasionally Philippe Dupuis and I chatted on the phone. He told me that Alcatel had been in to see the French PTT at a senior level. They had asked for time. They had used their subsidiaries in a number of European countries to test out the strength of the CEPT position. The intelligence they got back was that a number of European Administrations might be persuaded to change their minds. Their engineers spent a hectic weekend writing up a huge technical report. They went a bit over the top. Every single parameter in the one page table produced by Ted Beddoes had been inverted. The wide band TDMA standard was presented as being superior on every single count.

An Alcatel road show started to travel around Europe. Bernard Mallinder kept me up-dated on where they were and where they were heading. Switzerland was their first port of call.

Armin Silberhorn in Germany and I were in touch on a regular basis. It was usually at home when I phoned since any spare moments were usually at the end of the day and the German working day was over. (Germany was one hour ahead of us). Within in short time his wife must have got an impression of a lodger moving in. A voice would shout to some distant room “Armin! it’s Stephen”.

The German Minister had ordered them to do an in depth technical reappraisal. The technical studies required information from the manufacturers. The information they received was contradictory.

One Thursday night we chatted on the phone. He was in a particularly good mood. “On Monday there will be a battle of the giants at the Darmstadt technical centre” he announced. “Alcatel will be confronting Ericsson in front of the German PTT technical experts. The outcome will influence what recommendation is put to their Minister.”

This was a very clever initiative. Alcatel clearly had mastery of the wide band TDMA technology and Ericsson were one of the most widely respected telecommunications systems companies and under the leadership of Ulf Johansson their mobile division were powered up the learning curve of narrow band TDMA.

But this news also rather concerned me. The ink was still wet on the Alcatel study. To have all that new material suddenly sprung at a confrontational meeting was akin to throwing sand in the eyes. A fair debate required everyone to have the same basic data. Only in this way was a fair peer review possible.

The next day Bernard Mallinder told me the Alcatel team were in Italy to see the Italian phone company SIP. After lunch I telephoned Renzo Failli. He confirmed my fears. Alcatel had bombarded the SIP officials with graphs, equations and measurement data. Renzo was astute technically and very much on top of the new digital technology. But even he didn’t pretend to have understood most of it. I asked him whether he could fax the Alcatel report to me. He exploded. “It’s over two centimetres thick”. We had a haggle and eventually he faxed the key chapters.

It was thick. It took about an hour to receive all of it over the fax machine. By the time I sat down to scan the report it was past 6 pm on a Friday night. It was as obtuse as I had feared and time had run out for Armin to do anything. There was only one option. I resolved to get the report up to Ericsson that evening.

I telephoned Ulf Johansson of Ericsson. I couldn’t get him at his office. Somebody gave me his home number. He wasn’t home either but his son promised to pass on a message. About half an hour later he phoned back. He was very interested for his engineers to see the report before going to Darmstadt on Monday. He gave me a fax number.

By this time the DTI staff running the fax machines had long since gone. The duty officer turned out and opened the communications room. We were confronted with a fax machine, which looked more like a giant computer. The duty officer shrugged. He left me struggling through the fax handbook. I thought I’d got the hang of it. The document in its entirety passed through the machine. I telephoned Ulf to see if it had been received. Ulf in turn phoned his duty room. It hadn’t arrived. Back to the handbook. Some commercial attaché in Africa would be having a puzzling time on Monday morning trying to fathom the technical gibberish sitting in the fax in-tray! I tried again and telephoned Sweden. This time success! I left the DTI building very late that night.

The great battle of the industrial giants took place in Darmstadt. It seemed that Ericsson had given a good account of themselves. The Alcatel engineers had been caught out on a number of points and had to retract some claims. It was only a small a step along the way but only part of a much bigger struggle taking place in Germany.

Alcatel had done a very good lobbying job at the highest political circles in Germany and managed to convince them that Alcatel SEL had the most advanced mobile radio technology which had to be exploited in the best of German mobile radio customers. Documents were being supplied by SEL to politicians that were not being passed down to the officials responsible for GSM. Armin Silberhorn had a big challenge on his hands. One of the first things Armin did was to cut himself into the flow of the Aclatel-SEL lobbying documents hitting the Ministry at high levels and ensured that they all received proper expert scrutiny.

On the 24 and 25 of February Armin held a workshop between the Ministry and their technical arm FTZ to plan the way forward. Frieder Pernice was involved and Friedhelm Hillebrand was asked to help. On 11 March 11 the Minister Dr Schwartz-Schilling ordered the President of FTZ to carry out an internal examination of the two rival technologies. This took place in Koblenz and it was down to Armin, Frieder Pernice and Fred Hillebrandt to defend their preferred position of narrowband TDMA. This won the day and led to a recommendation to the minister for narrowband TDMA. A week later the President of FTZ presented his findings to the Minister and recommended the narrowband TDMA solution. Armin and Fred participated in the meeting. Armin asked the Minister directly whether the decision was to be based only on technical and commercial criteria or whether there were any other criteria or factors influencing the choice. This was to flush out whether industrial policy was to be a factor in the choice or not. The Minister said that the decision should rest on just the technical and commercial criteria and endorsed their recommendation.

The German Minister was in no rush to make his decision known to the rest of Europe. He had a political agreement with the French to cooperate over the digital cellular radio project. He reasoned that if his experts came to a certain technical conclusion that narrowband TDMA was better – why were the French not coming to the same conclusions? He ordered Armin Silberhorn to go to Paris and prepare a joint technical report with the French Officials.

Armin, together with Fred Hillebrandt and Frieder Pernice went to Paris, on March 18. On the French side was Philippe Dupuis, Bernard Ghillebaert and Alain Maloberti which they had expected. But the surprise was to see that the French PTT had company. The head of Alcatel’s mobile communications was there. There followed a long and inconclusive discussion followed by a long lunch.

Over lunch Philippe Glotin, the senior executive from Alcatel, told them about the moves by Vodafone to get access to the GSM channels. He noted that this was likely and once this was conceded then the UK would be out of the GSM game.

After the lunch Philippe Dupuis and Armin Silberhorn went back to prepare their joint report. The gist of it was that, whilst the GSM may have over stated the advantages of the narrow band TDMA at Madeira, overall it remained the best technical and economic choice. A copy was faxed to me.

I learnt later that Philippe Dupuis paid a high price for this technical report. His chief tore it up, re-wrote it himself, added the conclusion that the wide band TDMA solution was right for the French situation and then put it up to the French minister. The manufacturing advantages was being given a higher priority than the needs of the mobile service business.

Ever since the Madeira meeting, when the French Prime Minister’s office had become involved, Philippe Dupuis had exercised less and less control over events. It had become far too political and driven by the industrial policy side of the French PTT. But at least he was in the thick of the action. After the meeting with Armin Silberhorn he was simply cut out by those at the more political level now driving things. He did a wise thing in the circumstances, took some leave and went skiing.

The German Minister’s next move was to send his Senior Officials led by Mr Haist to agree a common line with the French. The meeting was to take place on March 25th 1987 with M Roulet leading on the French side. Armin Silberhorn told me the evening before that the meeting was to be a show down. The Germans proposed to take a tough line. They would be sending a note to all the other CEPT Administration telling them that Germany proposed to adopt the narrow band TDMA solution. It was up to the French to associate themselves with this or go their own way.

The report I got from Armin the following evening was one of despair. Yes the German team had started out with a tough line. All had gone well until the lunch break. Over lunch the French side suddenly sprung the idea of more comparative trials. One of the German party responsible for procurement immediately reacted enthusiastically and said that he happened to have some money left in his budget for this. The head of the German team wavered and the tough line disintegrated.

Upon hearing this from a very depressed Armin I immediately faxed a note to Martin Boyle at our embassy in Paris asking him to go in to see the French PTT and tell them that the UK government viewed further tests as a waste of Europe’s time. By complete coincidence he and his chief had an appointment with an official in Minister Longuet’s cabinet the next morning.

Minutes before the UK embassy officials arrived for the meeting the report of the Franco-German meeting proposing more tests landed in the in-tray of this top Cabinet official. He only had a few minutes to glance at it when in breezed our men in Paris saying what a complete waste of time these extra tests were. The French Cabinet official went into orbit. How did the British (of all people) get hold of such a sensitive report even before he had even read it.

That furthered the cause of Anglo-French understanding !

It was time to reflect. The UK had become effectively no more than spectators. Voyeurs even. How could we cut ourselves into this dialogue? I got up and fetched a copy of the Quadripartite agreement to study. Up until now the French and German Administrations had been doing no more than GSM had asked them to do. Reconsider their position. Fresh trials were a whole new ball game. Whatever happened to the Quadripartite Agreement?

On Monday 30th of March I sent Armin Silberhorn a very formally worded diplomatic style note. It reminded him of the written obligations his Administration had entered into which referred to working with the other three partners. Why were they now only working with only one other partner in what was clearly a new phase of activity? Italy and the UK had a right to be told the present German preference.

Armin was not happy to receive the note. Yes he agreed that I had a point but the Germans also had a specific agreement with the French. Which took preference? He would consult his chief.

Next day Armin telephoned me. He asked me whether I could get our Minister Mr Pattie to send his Minister a note saying that proposals for fresh trials had to be first discussed amongst the four countries. “What if Mr Pattie phoned his Minister? I asked. Armin like this idea even better. But it had to be done before Friday lunchtime. Why so soon? This forced him to reveal that on Friday afternoon on the 3rd April the French had arranged for their Minister to telephone his Minister.

I phoned Mr Pattie’s private office. My heart sunk when they told me that Mr Pattie was in the USA. He wouldn’t be back until late Thursday afternoon. That made things very tight. I took a deep breath and asked his private secretary to put the telephone call in the Minister’s diary for Friday at 8am.

On Friday I arrived at my office at 7.30 am. It was agreed that we would initiate the call. The previous day I faxed to Armin a copy of the brief I’d put up to Mr Pattie. There was to be no scope for misunderstanding.

At 8 am there was no sign of Mr Pattie. Was my luck about to run out? At three minutes past 8 the German Minister’s office telephoned us. Mr Pattie’s private secretary took the call and spoke in fluent German. I was quite impressed. I hissed to him to ask how tight the German Minister’s schedule was. With some relief we were told that he was free for several hours.

After 15 minutes Mr Pattie arrived cursing the traffic.

The call was put through. Afterwards Mr Pattie told me that the German Minister had recounted the history of the initiative and said that when the project started he hadn’t dreamed that so many versions of the digital technology would emerge. He expressed his preference for the narrow band TDMA but baulked about going public. He owed this to his French colleague. However, he agreed that hence forth all activity should take place within the group of four countries!

Mr Pattie had pressed him on time scales. They agreed that senior officials from the four countries should meet and try and find a solution. If this was not possible the four Ministers should then meet in Bonn. Mr Pattie extracted from him that this should be envisaged before the end of May.

The German Minister and Mr Pattie had changed the game. The inner circle of just France and Germany had now been expanded formally to include the UK and Italy. We were still some distance from an agreement but the world had just changed.

As I left the Minister’s office the DTI officials for his next meeting trooped in. Sale of Rolls Royce.

The Germans busied themselves setting up the meeting of senior officials. A date of 23rd April was set. I busied myself with other problems crossing my desk. But I had occasional forays to further our prospect. With the appropriate clearance…a discrete briefing to David Thomas of the Financial Times for example. He was an incredibly good reporter who was following the story closely. What really impressed me was the diligent way he would check back to get the detail right.

GEC telephoned me and asked if I would be prepared to see Philippe Glotin from Alcatel. He was visiting them and had asked if GEC could arrange a meeting with me. It was a very friendly meeting. I was impressed with his intelligence and commercial astuteness. He had a statesman like quality. I told them of the overall strategy I’d been discussing with other European colleagues in order to get the market moving. Later he told the GEC man that he had learnt more from me in five minutes on what was going on in Europe than the French PTT had told him in totality.

At the meeting Mr Glotin then turned to the real reason for his visit. Alcatel wanted to become the second French mobile operator. Motorola and Alcatel had an interest in getting a TACS network up and running. The French military were being difficult in releasing any 900 MHz frequencies. Some hush hush system. Could I get my Ministers to apply pressure on the French government? I said that I didn’t think we had those sorts of lines of communication with the French at the present. Further, I was not sure it was in our interest in view of our commitment to GSM. The matter was dropped.

What came across to me from this meeting was that the French establishment was also working to keep GSM on track by defending the GSM frequency channels against commercial pressures to implement an analogue cellular radio system in the same way as I had been doing in the UK.

Some time later Alcatel lost interest in being the operator of the second French cellular radio network. The French PTT had told them bluntly that either Alcatel was a supplier to the French PTT or an enemy. They could choose.

A week later I was in Brussels at a technical conference to give a paper on European developments in cellular radio. The audience was packed. The GSM standards impasse was a hot topic. My paper examined the interplay between competition and co-operation in making a success of high technology in Europe. I could feel the audience warming to my theme. My usual approach in my public papers was to give a paper with 90% good common sense perhaps wrapped up in an imaginative way. Then other 10% was the DTI message that justified the public expense for the trip. The 10% on this occasion was to paint the virtues of competition in the provision of mobile services. My theme was that co-operation was needed to create the standard but competition was essential to drive it into the market. I plugged the narrow band TDMA technology – of course. The 90% was my prediction that European industry had to adjust to the fact that cellular radio was in process of adjustment from a professional electronics industry to a consumer electronics industry.

The questions afterwards were lively.

In the margins of the Brussels meeting I briefed Philippe Dupuis on the telephone conversation between Mr Pattie and Dr Schwartz-Schilling. I also briefed Philippe Glotin in great detail on the Ministers’ phone call. It was a risk but the right decision.

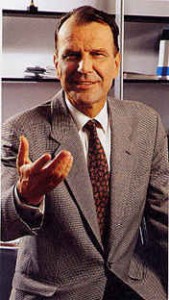

Figure 27 – Philippe Glotin from Alcatel took the key decision for France to support narrowband TDMA

He was a man one felt instinctively able to trust. He replied that he had guessed as much but that SEL were painting a much rosier picture of being able to turn the German government around to supporting the wide band TDMA. The very next day Philippe Glotin reported back to Alcatel that the support for the narrowband TDMA was overwhelming and the company took the fateful decision to no longer pursue the wideband TDMA technology but this did not emerge for several more weeks.

Other forms of contact were taking place in parallel with these events. In the middle of March I had arranged a meeting between the four large countries on an EC Research and Development programme called RACE. The aim was to align our views on the content of the programme. A lunch was arranged at Lockets. One of the senior German officials from their Research Ministry took me to one side afterwards. He had given SEL their research contract for developing the wide band TDMA system. He suggested that the best way to find a solution would be to let the leading European suppliers get together quietly and make a deal. He suggested that GEC could be a major player if the DTI would come behind the wide band TDMA solution. It was far to late in the day for this sort of horse-trading.

The next social encounter turned out to be less cordial. The French PTT had opened an office in London. It was one year old. A party was thrown towards the end of March. A large number of officials flew in from France from the Director General down. The French must have made up their guest list from a who’s who of the UK telecommunications sector. The number two at the French DGT was M. Grenier. He circulated around the cocktail party. I was itching to put the narrow band TDMA case to him. He eventually arrived nearby. The conversation started in a low key noting how well we were co-operating on the EU RACE R&D programme and some areas of EU legislation. What a pity that we had this problem with the digital cellular radio standard.

M Grenier said that he had personally put up the recommendation to his Minister in favour of the wide band TDMA standard. He said that in France all the demand was in the towns. The wide band TDMA standard was more economic in the cities (which was true). Thus he had concluded that the wide band standard was better for the French situation. I noted that their present experience with their public mobile radio system seemed to suggest the complete opposite. They had a system only covering Paris and one covering the whole of France. They were only charging half the tariffs for the one covering Paris but they still had a massive waiting list for the service covering the whole of France.

He then veered to the industrial advantages. My response was that mobile technology would be moving towards the consumer mass market in the 1990’s. I doubted whether France and Germany alone could make a success. Their markets were not even in phase. I paused but then went too far and tossed in that France were blocking any European agreement on GSM! Perhaps I just felt the need to speak for Philippe Dupuis who had been side-lined in the French PTT. At this M Grenier lost his temper. He said that he could respect my previous arguments but what I had just said he didn’t like at all. A French diplomat quickly intervened to talk about other things.

On Monday a colleague in the French PTT told me that news of our row had spread around the French PTT.

The date set by the Germans for the meeting of senior officials in Bonn was approaching. Still no solution was in sight. I was at a meeting in a British Telecom building one morning. The cellular radio in my brief case rang. I excused myself and went into the corridor to answer it. Philippe Dupuis was on the other end. He was telephoning from a chalet in the French Alps. He was just about to go up onto the ski slopes. A friend in CNET (the research arm of the French PTT) had contacted him. Alcatel had been into see them asking whether the narrow band TDMA solution could be changed slightly so as to enable them to salvage something from their wide band TDMA development work. He thought he would pass it onto me for what it was worth.

The following week I was on a plane to Rome. From there I would fly onto Bonn for the four-country meeting. The purpose of the Rome trip was far from clear. Mr Butcher the junior minister had visited Rome a few weeks earlier. He had been well received everywhere he had gone. I was sent down to “follow up” his successful visit on the recommendation of the UK embassy.

My visit coincided with Mercury being in Rome to try to secure interconnection of their switched telephone service to Italy. They were having the greatest difficulty in getting any interconnection agreements with the rest of Europe. The local UK embassy official took me uninvited to the Mercury meeting with ASST, who were responsible in Italy for European connections. We were not exactly made welcome. The UK embassy man kept nudging me that I should say something. The Mercury team were being given quite a hard time. Just before the lunch break I gave a strong speech extolling Mercury as the chosen second force in UK telecommunications. I pointed out the strength of Cable and Wireless behind them. I felt sure that they would act to increase the total traffic between the UK and Italy to mutual benefit. It had the UK Embassy man nodding vigorously. It didn’t seem to please the head of the Italian side.

On our way to lunch the head of the Italian side took me to one side. An interconnection with Mercury was an irritation as far as they were concerned. All the hassle and what were Mercury able to offer ? A few percent of what British Telecom were delivering. On the other hand if it was that politically important then providing it didn’t cost them anything, they were prepared to go along with it. I passed this on to the Mercury representatives. Almost exactly the same sequence of events took place in Germany at I meeting I had set up for Mercury. Mercury was given a very hard time in the morning. Then two German colleagues took me quietly to one side on the way to lunch. They talked about the hassle for a few per cent of traffic. But they also were curious as to why I was pressing them so hard. They could understand that a show might have to be put on in front of Mercury but did the DTI really want the German PTT to damage BT, the UK national flag carrier?

The story helps to illustrate the climate in Europe in the mid 80s in which we operated and just how out of step the UK was with the rest of Europe in opening up its telecommunications market to competition.

The rest of the trip was exchanging some pleasantries with a large number of Italian officials. On the flight to Bonn I asked on the plane for a Financial Times. What a surprise to see a leading editorial about the pressing need to unblock the digital cellular standards issue. What impeccable timing just prior to the meeting of the four officials. It was not of my doing and it further enhanced my regard for the FT and the late David Thomas.

The Bonn meeting started in the evening with a dinner of senior officials. The French Director General broke the news that the French were prepared to compromise. We must be prepared to make slight adjustments to the narrow band TDMA solution. These were identified. Essentially the French wanted to knock out the piece of the package deal that the Norwegians had got. During the dinner I had a real go with one of the French experts sitting next to me who had been at Madeira when we’d settled the package. His view was that this was the French price of a settlement. They had to support the interest of their industry.

Figure 28 – Torleiv Maseng, Norwegian researcher, loses in the industrial power play, but has a place in GSM history

After the dinner Robert Priddle asked me what I thought. I said that it would anger the Scandinavians but they would probably accept it. The solution the French were pushing was slightly less efficient but offered industry slightly more flexibility in implementing receivers. As a price for a European deal we had little choice but to go along with it.

(Note: Having read my account in December 2009 Alain Maloberti sent to me an alternative view. It is very insightful and readers may find it interesting to read this technically oriented perspective alongside my more politically oriented account at the end of this chapter). That noted, we now return to Bonn in 1987:

At the meeting next day the deal was put on a more formal basis. The French and Germans had a haggle about a technical feature called frequency hopping with the French liked and the Germans didn’t. I fielded a compromise which they both accepted.

There was no more perfect time to launch my second parallel plane of activity than this Bonn meeting. Robert Priddle had cleared the intention to raise the issue with the German senior official who was chairing the meeting.

As the meeting of senior officials past its critical stage on the technology dispute Mr Haist the German senior official turned to me and invited me to present my analysis of the commercial prospects for GSM and the need for a commercial strategy to get it to market. The bottom line was that a new initiative was needed to draw up a commercial operators agreement. I proposed that Ministers of the four countries should instruct their officials to draw up such an agreement and for this to be ready for signature by September of that year. Everybody supported this. A group of experts were charged with sorting out the details of the modified technology package deal sought by the French and exploring further my suggestion for the commercial operator agreement to implement GSM.

All was now ready for the meeting of Ministers in Bonn on the 19th May 1987.

1. FOOTNOTE from Alain Maloberti:

Alain: “One of the things that Torleiv got right in the first place with the proposal he made late 1986 was to have a sufficient amount of redundancy in the signal to better protect it from propagation impairments. The other NB-TDMA propositions either did not include any redundancy (which led to disastrous results) or include (for fear of losing too much bandwidth) a too small amount: this is one of the reasons for the better results (notably in spectrum efficiency) in the Paris trials.

However, contrary to all the other proposals, this redundancy was put in the modulation and not in a separate channel coder. This both increased the complexity, and prevented a proper efficiency of the error correction at very low speed (typically pedestrian usage), which was much better handled by a simple modulation, with an added independent error correction combined with frequency hopping. This has indeed proven very efficient later both to ensure hand-held quality for slowly moving customers, and better spectrum efficiency when fractional reuse was introduced (mainly by Ericsson in the first place).

So the discussion was held on purely technical grounds and the new scheme considered better and certainly not “less efficient”. It is fair to say that this on-going discussion provided Alcatel (and possibly also the French ministry) with an excuse to get out of the corner they were and rally the majority camp still holding their head up, but the change was technically sound and has proven so. I remember that you always thought the choice of the modulation scheme to be political, and we discussed a lot together in Madeira as I was not in favour of including this in the set of working assumptions: I was convinced that we should be able to get a technical agreement. The inclusion was not so bad after all, since its change gave an excuse to some proponents to join the NB-TDMA camp later; so we both were right in some way.”

2. FOOTNOTE from Jan Audastadt

Jan: “The next GSM meeting after the May Bonn meeting of Ministers (covered in Chapter 17) occurred in Brussels in June 1987. Before the main meeting started Bernard Ghillbaert (France) and Fred Hillebrand (Germany) invited me to a discussion on the earlier GSM Madeira decisions that the choice of modulation for GSM should be based on the Norwegian test modem. Bernard Ghillebeart and Fred Hillebrand put the case to me that Norway should not insist on using the complicated modulation method of Maseng’s modem but accept a simpler one (see Note 1 above). I had no problem to accept this request. This allowed a unanimous decision by the whole of GSM on its first technical specification of “Working Assumptions” for the GSM radio air-interface “